Foam Alone? Citizen Science Data Reveals Weak Link Between Foam and Water Quality on the River Mole

- Oct 18, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Apr 24, 2025

Foam on the Mole

Foam is a common sight on the River Mole and is typically associated with pollution. It is frequently mentioned on social media, sparking debates on its origins and potential harm. This post examines nearly two years of citizen science data taken from across the river catchment analysing the patterns and causes of foam.

Foam can result from both natural and human sources and our findings show that foam, alone, is not a reliable indicator of water quality in the River Mole catchment. We explore how foam levels vary seasonally and geographically, as well as the relationship between foam and other pollutants in the River Mole catchment.

These are preliminary findings albeit from a substantial and growing data set. Our ongoing citizen science will provide deeper insights as we gather more information, helping to better understand foam's role and impact on the River Mole.

Before we dig into our data, here's some context on what we know about foam in rivers, courtesy of the EA and other sources.

Not all river foam is the same. Foam can be caused by natural and unnatural sources. Data suggests we have different causes of foam at different places on the River Mole.

Foam isn't always bad... even though it may appear undesirable, a certain amount of foam indicates the presence of organic matter which is essential for healthy rivers due to the energy, nutrients, food, habitat, refuge areas, structure and complexity it adds to a stream system.

Natural foam occurs when organic matter, such as decaying leaves and vegetation, breaks down and natural compounds and oily chemicals are produced. These oils, or surfactants, are buoyant and float to the surface, reducing surface tension and creating bubbles. Turbulence can introduce air into the organically enriched water, generating more bubbles. Without surfactants, bubbles would only last moments before bursting but with surfactants they persist and build up as foam.This type of foam is usually harmless and is common at points where turbulence occurs such as weirs.

Some foam is "manmade". Such unnatural foam can come from several sources:

Detergent: Numerous sources including misconnected drains, car washes, road runoff and industrial effluents can introduce detergent chemicals used in cleaning products, cosmetics and shampoo/toothpaste or soaps into the river which cause foam to form. Unlike natural foam, detergent foam usually accumulates near a point source.

Sometimes foam can become excessive and build up to great depths in acute situations downstream of polluting industries either due to release by accident or inadequate treatment. For example, the "toxic foam" shown above in River Yamuna in India in 2021, was reportedly caused by discharges of detergent from garment making factories in addition to poor treatment of sewage failing to extract household detergent.

Fertilisers: Excessive nutrient runoff from agriculture can lead to algal blooms. When these blooms decay, they can cause foam and reduce oxygen levels, harming aquatic life.

PFAS: Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances or "Forever Chemicals" are used in a huge range of products like firefighting foams, cosmetics and water-proof coatings. Due to it's water-repellent properties PFAS can cause foam to form on rivers. PFAS foam usually appears bright white, lightweight and sticky. The widespread presence of PFAS nationally and globally is a growing environmental and human health concern. Tests have shown the presence of PFAS all over the country including at sewage treatment works in the Mole catchment. Hot spots of PFAS contaminated sites are being brought to light by the valuable work of our friends at the incredible Watershed Investigations.

PFAS levels, River Mole catchment Given the persistent nature of PFAS in the environment and the confirmed presence of these substances in the catchment area, it is prudent to assume some concentration of PFAS might exist within the foam seen on the River Mole, regardless of its original source. Nevertheless, evidence suggests foam on the Mole has immediate causes other than PFAS.

Citizen Science Methodology

Below is a summary of two-years of monthly foam data collected by our citizen scientists. They gathered more than 1000 reports on foam and visual pollution from 33 test sites throughout the River Mole catchment. Data collection is ongoing so this is a preliminary study of what our results show so far.

Each month our trained volunteer citizen scientists survey their test site and conduct a variety of chemical tests for numerous pollutants, as well as taking measurements of conductivity and temperature. In addition, observations are made including visible signs of pollution and a specific survey on the extent and coverage of any foam on the river as shown below.

A simple numeric scale is used to record foam observed on the water course from 0 being no foam visible, 1 small patches to 3 extensive large cover and 4 complete coverage.

Foam Survey Results

Seasonal trends

The results show a clear seasonal trend in levels of foam. The chart below shows average seasonal level of foam for the catchment increases significantly through Autumn and Winter before decreasing in Spring to reach a low in Summer. Notably both summers for which we have data recorded low foam scores.

The line chart below shows month by month changes in average catchment foam scores. It shows the highest foam score was recorded in January 2023 and lowest foam scores were recorded both July 2023 and July 2024.

The seasonal pattern looks likely to be associated with river flow (known as discharge). The chart below shows average catchment river discharge on the day of the monthly test and the average foam score. Levels of reported foam are seen to follow river levels quite closely.

Casual observations support a connection between river levels and foam amounts, suggesting that higher flow periods typically result in more foam. The images below demonstrate a snapshot of this phenomenon, showing increased foam at Castle Mill in Dorking in April compared to lower foam levels during low flow in August at the same location.

The pictures above were taken just below the weir at Castle Mill. As shown in the photographs below, foam tends to be created at such weirs due to turbulence especially at high flow.

The same foaming effect has been observed at many weirs, large and small, up and downstream along the river including examples on the Upper Mole at Tanners Brook, Brockham, to the Middle Mole at Leatherhead weir and the giant sluices on the Lower Mole through Esher and Molesey.

A more granular look at seasonal change in foam levels shows further patterns along the main channel.

Most sites on the main channel tended to show peaks in foaminess in winter, for example Gatwick Stream at Horley. However there are notable exceptions such as the Lower Mole at Ember which peaked in Spring.

With higher river levels comes increased sewage storm overflows from the 9 big sewage works in the River Mole catchment. There appears to be a reasonably strong correlation between levels of foam and the duration of untreated sewage storm overflows as shown in the scatter chart below.

However, correlation does not mean causation and our data suggests that the apparent link between foaminess and duration of raw sewage outfalls does not fully stack up. Indeed, the data in the chart below suggests the reverse! For much of the year, streams with sewage treatment works are less foamy than ones without. This is particularly the case during Autumn and Winter when river levels are generally higher and therefore when storm overflows are more frequent. From this data, on a catchment scale, the most foamy streams are the ones without sewage treatment works.

It seems likely that the apparent link between foam scores and storm overflows is due to the higher river levels associated with rain and longer storm overflow duration rather than the sewage discharge itself. The chart below shows some correlation between foam and rainfall which, whilst weak, may support the idea of rainfall causing a rise in river levels that ultimately leads to more foam.

Below are the key summary points from this section:

A strong seasonal pattern suggests that foam levels tend to rise during winter and decrease in summer.

The data suggests a correlation between higher river levels and increased foam presence.

On average, streams with sewage treatment facilities appear to have less foam compared to those without.

Observations indicate that weirs within the catchment area tend to generate foam, especially during periods of high flow.

The strong seasonal pattern, location around weirs and disconnect with STWs likely suggests most of the frequently observed foam has a natural origin associated with increased load of organic material.

Next, we will examine streams with the least and most foam in the catchment and investigate whether there is a correlation between foam levels and pollution levels. If we first concentrate on tributary streams instead of the main channel, it is notable that there are striking differences in foam levels between different streams, sometimes close neighbours with differing pollution levels. Therefore, the question arises: to what extent is foaminess connected to pollution levels?

Is there a correlation between foaminess and pollution levels?

Low Foam Streams

Several streams have recorded no foam at all over the two years of surveys. Examples of "no-foam" streams include Ifield Brook, Hookwood Common Brook, Spencers Gill and Peeks Brook (Burstow Stream) all in the Upper Mole basin. These streams include two relatively rural streams draining small agricultural catchments that are recognised as highly polluted: Hookwood Common Brook and Spencers Gill. Low foam streams also include two tributaries which rate as some of the least polluted streams in the catchment: Peeks Brook and Ifield Brook.

Several more streams have recorded very low levels of foam over the two years including Bewbush Brook, Burstow Stream at Lake Lane and Leigh Brook.

Whilst Bewbush Brook is ranked as the least polluted water course in the catchment, Leigh Brook consistently ranks as the most polluted. Yet, both have low foam scores.

Low foam levels found in polluted rural streams draining farmland seems to indicate that agriculture is not likely to be a key source of foam.

High Foam Streams

The foamiest streams in the River Mole catchment are Deanoak Brook, Wallace Brook, Gad Brook, Tanners Brook and the Rye. These all drain relatively rural sub-catchments with Deanoak, Wallace and Tanners Brooks having predominantly agricultural land use while the Rye drains from residential areas in it's upper reaches. They all have peaks of foam levels from Autumn through Winter to Spring which follows the catchment pattern.

The most foamy streams in the Mole catchment are around "mid-table" in our rank order of most polluted streams with Wallace, Tanners, Deanoak, The Rye and Gad Brooks coming 10th, 11th, 13th, 14th and 15th respectively in terms of water quality. Earlswood Brook is an unusual tributary and comes somewhat lower in the league table of "most polluted" at 20th out of 33 water courses. (33 being the most polluted stream which is Leigh Brook).

The more foamy streams again appear show no strong link between the level of foam and the underlying level of pollution and water quality. Some of the most polluted streams in the catchment are least foamy and some of the least polluted streams record higher levels of foam.

Overall, data for the River Mole appear to suggest the level of foam is not a reliable indicator of water quality.

The charts below support this general lack of correlation in the data between the level of pollution and the level of foam. There might be the suggestion of a weak positive link between conductivity and foam score. In addition, there might be the hint of a negative correlation between phosphate levels and foam but these are far from conclusive. As we gather more data things might well change but, for the moment, our data suggests that the presence of foam in the River Mole does not relate strongly to water quality.

In short, Foam alone is not a good indicator of pollution.

Earlswood Brook: Acute Foam Story

Overall, Earlswood Brook has a "low to moderate" foam score but suffered a particularly acute foaming event in March 2023. It is a first order stream (no tributaries) and picks up a large proportion of its flow from Earlswood sewage treatment works to the south of Reigate/Redhill. As much of the volume of the stream is treated effluent it is no surprise that it has a lower water quality, often recorded as Poor in our water quality tests.

In March 2023 a blanket of foam was reported by River Mole River Watch members covering the stream for over 30 metres and building up into some depth against low branches and vegetation before breaking up into smaller patches and travelling several hundred metres downstream. The foam was easily traced upstream to the sewage pipe outfall from Earlswood Sewage Treatment Works.

The scene was reported to Thames Water and the EA by members of River Mole River Watch. A Thames Water team came out quickly and reported that this foam was "Final Treated effluent discharge".

We were informed there was little immediate risk to aquatic life though we strongly countered that there could be a risk of detrimental impact to ecosystem health and furthermore that such persistent foam was an environmental eyesore to residents. The EA later reported to us that effluent treatment at the sewage treatment plant would be adjusted to reduce future foaming. We haven't had reports of extensive foam since but updates on foam levels from any recent visits are most welcome.

What we learned from Earlswood Brook

Acute foaming like this is comparatively straightforward to trace back to the source.

The foam fitted the EA descriptor well for "unnatural foam" because it was bright white, rather soapy in appearance, quite localised, accumulated near the source, seemed not to be linked with different weather or flow conditions and tended to disperse downstream.

A problem with treated effluent caused Earlswood Brook to foam up and shows how foam scores might change rapidly on some streams with STWs.

White foam that is not weather or season related, not only appearing at weirs or in turbulent flow, and accumulating along a defined stretch is likely to be unnatural in origin.

If only all foam on the Mole was this easy to trace back to a source and find the cause!

Whilst some of the least foamy streams are those with sewage works, acute foaming incidents have been caused by problems with effluent treatment.

Overall, conclusions from what we have learned so far are as follows:

Streams show significant variability in foam levels, with no clear correlation between foam and pollution.

Some highly polluted streams have little to no foam, while less polluted streams can exhibit higher foam levels.

Low foam levels in polluted rural streams suggest agriculture may not be a primary foam source.

High foam streams generally rank mid-level in terms of water quality, further challenging foam's role as an indicator of pollution.

While some weak correlations between foam and conductivity or phosphate exist, they are inconclusive and require more data.

The March 2023 foaming event in Earlswood Brook was linked to treated sewage discharge, highlighting the need to be alert to the risk of occasional foam surges from point sources including sewage treatment works.

Geographic Distribution

Let's now analyse the geographic distribution of foam levels across the catchment: the map below displays small dark blue dots on streams with the lowest foam scores and larger light blue dots on water courses where the highest foam levels have been recorded.

Perhaps contrary to finding little catchment-wide connection between foam and pollution, most of the streams with lowest foam levels are found in the Upper Mole catchment, around and upstream of Crawley, where water courses also happen to be least polluted.

Tributaries with lowest foam scores are mainly low order streams (those with few tributaries) which rise from sources in the wooded hills on the watershed surrounding the drainage basin around Crawley. These include Bewbush Brook, Ifield Brook, upstream stretches of the Gatwick Stream and Burstow Stream. Bewbush Brook, for example, drains from the beautiful Worth Forest area and Buchan Park Lake shown in the photo above. This is an area with a low foam score and also low phosphate pollution levels. These Upper Mole streams with low foam and low phosphate levels are shown on the map below with green labelled boxes.

Other patterns emerge from the busy map above. Several streams have high phosphate levels and low foam scores. These are noted labelled above in red boxes and include Redhill Brook, Salfords Brook and Leigh Brook. (Note: Notwithstanding the acute foam event mentioned above, Earlswood Brook has a moderate average foam score overall). These streams might hint at an urban bias towards low foam scores with several high phosphate / low foam streams draining more built-up catchments in Redhill and Reigate. However, several rural streams draining from more agricultural sub-catchments are foamy, for example Wallace, Deanoak, Gad and Tanners Brooks. These are labelled in blue boxes on the map above. Gathering more data will help to see if there are any more robust connections between foam and land use.

It is important to highlight the significant variations in foam levels between neighbouring streams that have similar land use but are located very close to each other. For instance, Deanoak and Gad Brook exhibit high levels of foam, while Leigh Brook, situated between them, records considerably lower foam levels. Despite all three streams draining catchments with fairly similar characteristics of woodland and farmland on agricultural clay and low population density, Leigh Brook stands out for having the lowest foam levels among them but is, of course, the most polluted stream. This reinforces how foam, alone, is not a reliable indicator of pollution levels.

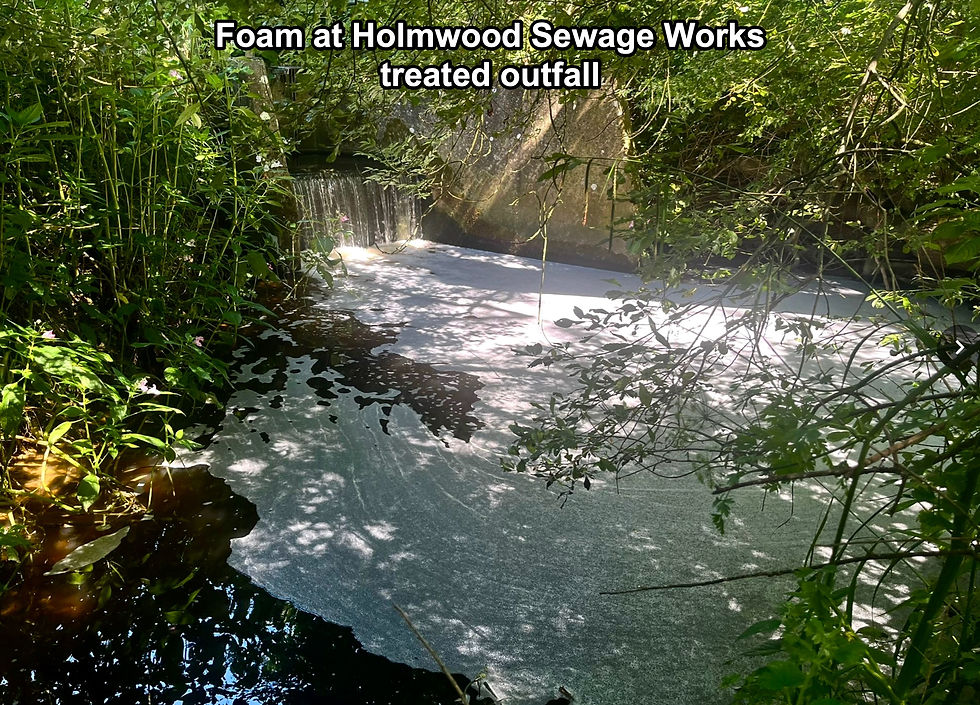

However, to complicate matters, a good deal of foam was seen flowing into the Leigh Brook at the outfall of Holmwood Sewage Works on a detailed testing day with the EA on the Leigh Brook in July. However, this foam dissipated very quickly downstream and was only associated locally with the treated effluent discharging from the works. Nevertheless, along with the acute foaming evidence from Earlswood Brook, this shows how sewage treatment works can be responsible for delivering foam to streams, albeit usually localised around the outfall.

For the catchment as a whole, from the relatively low-foam scores in tributaries draining from the watershed, there is a noticeable but varying increase in foam scores downstream, as illustrated in the chart below.

Whilst the upper tributaries have low foam scores and there is modest increase downstream, there is still a good deal of fluctuation between high foam sites found along the main River Mole channel. The most foamy stretches on the main River Mole are found at Horley Riverside on the Gatwick Stream, Castle Mill in Dorking, Leatherhead and Fetcham Splash and the Lower Mole at Ember.

In between the foamy sites, there are notably less foamy stretches, for example at Sidlow, the Stepping Stones, the Mole Gap and Cobham (West Vale is a comparatively new test site so foam observations are not as extensive). The fluctuation in foam downstream along the main channel may be due to specific test site characteristics and channel morphology. Sidlow Bridge, for example, is a pool of relatively calm, quite deep, laminar flow where there is usually little turbulence to cause foaming.

At the Stepping Stones, despite a reasonably turbulent flow past the stones themselves observations show there are only small foam patches created even at high river conditions.

Local weirs and riffles are clearly responsible for many of the high foam levels found downstream. However, the trend downstream showing a tentative rise in foam levels seems to suggest that the cause of foam is naturally occurring organic matter accumulating in the water downstream. Further study is needed to solve the true provenance of river foam but evidence so far seems to suggest most of the foam seen in the main River Mole channel is natural in origin.

There are of course numerous possible man-made causes of foam in the Mole catchment, some of which have been discussed already such as sewage effluent, PFAS or agricultural runoff. We will need to continue to collect more data to learn more about these and other sources of foam. For example foam from road runoff is a known point source as can be seen in the photo below by a main road in Crawley. In this example the foam was highly localised in a culvert but it is likely chemicals in the road runoff such as poly-aromatic hydrocarbons progressed invisibly further downstream and might froth up at weirs.

Overall, findings from this section on geographic distribution appear to show:

Foam levels are generally lower in the Upper Mole catchment, where pollution levels are also low, particularly in small, rural tributaries.

Despite similar land use, significant foam variability is observed between neighbouring streams, indicating no clear relationship between foam levels and land use or pollution. However, further data is needed to investigate connections more thoroughly.

Sewage treatment works, like Holmwood and Earlswood, occasionally contribute foam locally, but this is usually short-lived downstream.

Foam levels increase variably along the main River Mole channel, with turbulence at weirs and riffles being a key factor in foam formation.

Much of the foam in the main channel may be of natural, organic origin, though man-made sources like road runoff may also contribute and need more investigation.

Conclusions

Foam is complicated! However, key findings from the two years of data in the Mole catchment show a clear seasonal pattern, with foam levels peaking in winter and declining in summer. Foam tends to form near weirs and high-flow areas, with apparently no strong correlation between foam levels and pollution, as both clean and polluted streams exhibit varying foam presence.

The data reveals that foam on the River Mole is influenced by a range of natural and manmade factors. Seasonal patterns and geographic variation suggest that natural causes like organic matter breakdown, turbulence at weirs, and higher river levels during rainfall contribute significantly to foam formation. Our data tends to show that much of the chronic foam seen in the main River Mole is probably natural but that acute point pollution events from sewage treatment works can create excessive foaming but this is usually localised.

Nevertheless, manmade unnatural causes, such as detergent pollution, sewage effluent discharge, and the presence of PFAS, may also play an important role, though their visible contribution appears more localised for example around sewage treatment outfalls and outfalls from road drains. Overall, our data suggests that the foam typically seen on a daily basis near weirs or areas of turbulent flow and associated with higher river levels is not usually a reliable indicator of poor water quality and is most likely naturally occurring.

However, persistent white foam that accumulates outside of these parameters is something we should all be alert to and concerned about and report accordingly to the EA and Thames Water and to us here at River Mole River Watch.

Our ongoing mission to collect citizen science data continues with our aim to improve the River Mole for people and wildlife. I hope you have enjoyed this initial foray into our foam data .. please consider supporting us by clicking on the donate button on the website.

Please also LIKE this blog post and feel free to make helpful comments below to further positive and constructive discussion.

Some references

EA information on foam https://www.bristolavonriverstrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Foam-info.pdf

Foam report on Indian River Yamuna https://weather.com/en-IN/india/pollution/news/2021-11-10-causes-impacts-and-precautions-for-toxic-foam-in-river-yamuna-faq

Comments